Some Constraints & Trade-offs In The Design of Network Communications

- networks distributed-systems ipc

This post distills the content presented in the paper “Some Constraints & Trade-offs In The Design of Network Communications” published in 1975 by E. A. Akkoyunlu et al.

This paper focuses on the inclusion of Inter Process Communication (IPC) primitives and the consequences of doing so. It explores, in particular, the time-out and the insertion property feature described in detail below with respect to distributed systems of sequential processes without system buffering & interrupts.

It also touches upon the two generals problem which states that it’s impossible for two processes to agree on a decision over an unreliable network.

Introduction:

The design of an Inter Process Communication Mechanism (IPCM) can be described by stating the behavior of the system & the required services. The features to be included in the IPCM are very critical as they might be interdependent, hence the design process should begin with a detailed spec. This involves thorough understanding of the consequences of each decision.

The major aim of the paper is to point out the interdependence of the features to be incorporated in the system.

The paper states that at times the incompatibility between features is visible from the start. Yet, sometimes two features which seem completely unrelated end up affecting each other significantly. If the trade-offs involved aren’t explored at the beginning, it might not be possible to include desirable features. Trying to accommodate conflicting features results into messy code at the cost of elegance.

Intermediate Processes:

Let’s suppose a system doesn’t allow indirect communication between processes that cannot establish a connection. The users just care about the logical sender and receiver of the messages: they don’t care what path the messages take or how many processes they travel through to reach their final destination. In such a situation, intermediate processes come to our rescue. They’re not a part of the IPCM but are inserted between two processes that can’t communicate directly through a directory or broker process when the connection is set up. They’re the only ones aware of the indirect nature of communication between the processes.

Centralized vs Distributed Systems:

Centralized Communication Facility

- Has a single agent which is able to maintain all state information related to the communication happening in the system

- The agent can also change the state of the system in a well-defined manner

For example, if we consider the IPCM to be the centralized agent, it’ll be responsible for matching the SEND & RECEIVE requests of two processes, transferring data between their buffers and relaying appropriate status to both.

Distributed Communication Facility

- No single agent has the complete state information at any time

- The IPCM is made of several individual components which coordinate, exchange and work with parts of state information they possess.

- A global change can take a considerable amount of time

- If one of the components crashes, the activity of other components still interests us

Case 1:

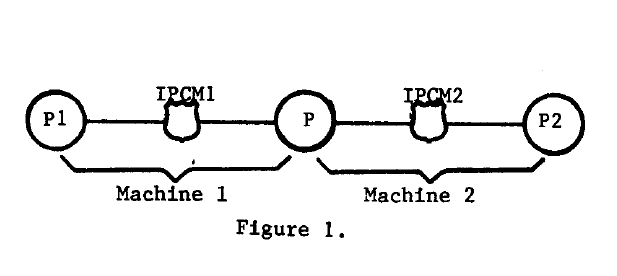

In Figure 1, P1 and P2 are the two communicating processes on different machines over a network with their own IPCMs and P is the interface which enables this, with parts that lie on both machines. P handles the details of the network lines.

If one machine or a communication link crashes, we want the surviving IPCM’s to continue their operation. At least one component should detect a failure and be able to communicate. (In the case of a communication link failure, both ends must know.)

Case 2:

Distributed communication can also happen on the same machine given that there are one or more intermediate processes taking part in the system. In that case, P, P1 & P2 will be processes on the same system with identical IPCMs. P is an intermediate processes which facilitates the communication between P1 & P2.

Transactions between P1 & P2 consist of two steps: P1 to P and P to P2. Normally, the status returned to P1 would reflect the result of the P1 to P transfer, but P1 is interested in the status of the over all transaction from P1 to P2. One way to deal with this is a delayed status return. The status isn’t sent to the sender immediately after the transaction occurs but only when the sender issues a SEND STATUS primitive. In the example above, after receiving the message from P1, P further sends it to P2, doesn’t send any status to P1 & waits to receive a status from P2. When it receives the appropriate status from P2, it relays it to P1 using the SEND STATUS primitive.

Special Cases of Distributed Facility

This section starts out by stating some facts and reasoning around them.

FACT 0: A perfectly reliable distributed system can be made to behave as a centralized system.

Theoretically, this is possible if:

- The state of different components of the system is known at any given time

- After every transaction, the status is relayed properly between the processes through their IPCMs using reliable communication.

However, this isn’t possible in practice because we don’t have a perfect reliable network. Hence, the more realistic version of the above fact is:

FACT I: A distributed IPCM can be made to simulate a centralized system provided that:> 1. The overall system remains connected at all times, and> 2. When a communication link fails, the component IPCM’s that are connected to it know about it, and> 3. The mean time between two consecutive failures is large compared to the mean transaction time across the network.

The paper states that if the above conditions are met, we can establish communication links that are reliable enough to simulate a centralized systems because:

- There is always a path from the sender to the receiver

- Only one copy of an undelivered message will be retained by the system in case of a failure due to link failure detection. Hence a message cannot be lost if undelivered and will be removed from the system when delivered.

- A routing strategy and a bound on the failure rate ensures that a message moving around in a subset of nodes will eventually get out in finite time if the target node isn’t present in the subset.

The cases described above are special cases because they make a lot of assumptions, use inefficient algorithms and don’t take into account network partitions leading to disconnected components.

Status in Distributed Systems

Complete Status

A complete status is one that relays the final outcome of the message, i.e., whether it reached its destination.

FACT 2: In an arbitrary distributed facility, it is impossible to provide complete status.

Case 1:

Assume that a system is partitioned into two disjoint networks, leaving the IPCMs disconnected. Now, if IPCM1 was awaiting a status from IPCM2, there is no way to get it and relay the result to P1.

Case 2:

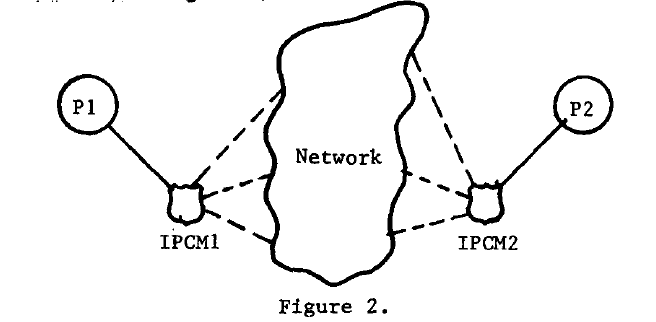

Consider figure 2, if there isn’t a reliable failure detection mechanism present in the system and IPCM2 sends a status message to IPCM1, then it can never be sure it reached or not without an acknowledgement. This leads to an infinite exchange of messages.

Time-outs

Time-outs are required because the system has finite resources and can’t afford to be deadlocked forever. The paper states that:

FACT 3: In a distributed system with timeouts, it is impossible to provide complete status (even if the system is absolutely reliable).

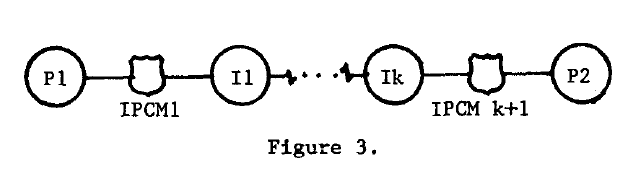

In figure 3, P1 is trying to send P2 a message through a chain of IPCMs.

Suppose if I1 takes data from P1 but before it hears about the status of the transaction, P1’s request times out. IPCM1 has now knowledge about the final outcome whether the data was successfully received by P2. Whatever status it returns to P1, it may prove to be incorrect. Hence, it’s impossible to provide complete status in a distributed facility with time-outs.

Insertion Property

An IPCM has insertion property if we insert an intermediate process P between two processes P1 & P2 that wish to communicate such that:

- P is invisible to both P1 & P2

- The status relayed to P1 & P2 is the same they’d get if directly connected > FACT 4: In a distributed system with timeouts, the insertion property can be possessed only if the IPCM withholds some status information that is known to it.

Delayed status is required to fulfill the insertion property. Consider that the message is sent from P1 to P2. What happens if P receives P1’s message, it goes into await-status state but it times out before P could learn about the status?

We can’t tell P1 the final outcome of the exchange as that’s not available yet. We also can’t let P know that it’s in await-status state because that would mean that the message was received by someone. It’s also not possible that P2 never received the data because such a situation cannot arise if P1 & P2 are directly connected & hence violates the insertion property.

The solution to this is to provide an ambiguous status to P1, one that is as likely to be possible if the two processes were connected directly.

Thus, a deliberate suppression of what happened is introduced by providing the same status to cover a time-out which occurs while awaiting status and, say, a transmission error.

Logical & Physical Messages

The basic function of an IPCM is the transfer and synchronization of data between two processes. This may happen by dividing the physical messages originally sent by the sender process as a part of a single operation into smaller messages, also known as logical message for the ease of transfer.

Buffer Size Considerations

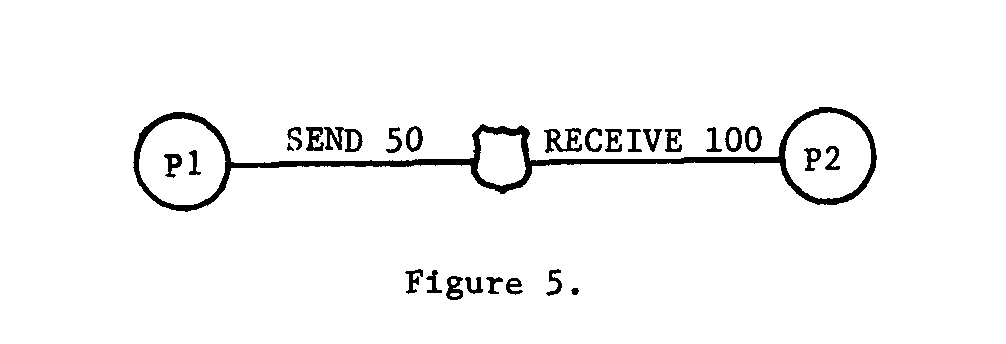

As depicted in figure 5, if a buffer mismatch arises, we can take the following approaches to fix it:

- Define a system-wide buffer size. This is extremely restrictive, especially within a network of heterogenous systems

- Satisfy the request with the small buffer size & inform both the processes involved what happened. This approach requires that the processes are aware of the low level details of the communication.

- Allowing partial transfers. In this approach, only the process that issued the smaller request (50 words) is woken up. All other processes remain asleep awaiting further transfers. If the receiver’s buffer isn’t full, an EOM (End Of Message) indicator is required to wake it up.

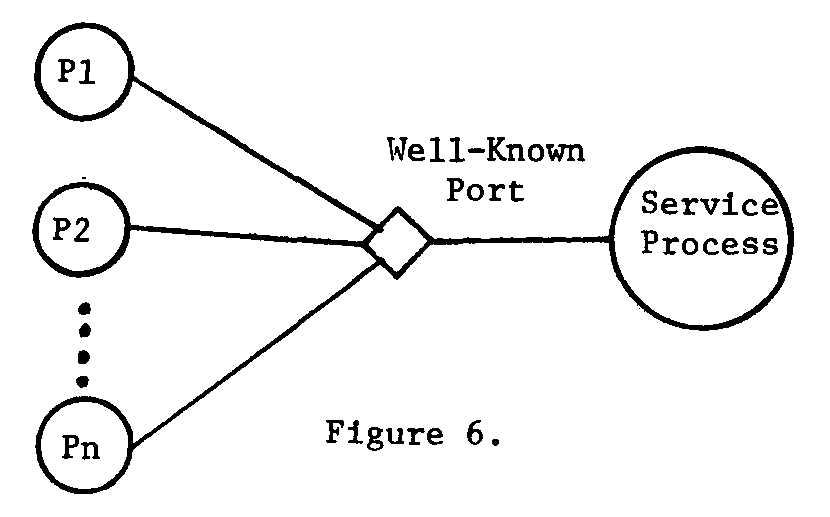

Partial Transfers and Well-Known Ports

In figure 6, a service process using a well-known port is accepting requests for sever user processes, P1…Pn. If P1 sends a message to the service process that isn’t complete and doesn’t fill its buffer, we need to consider the following situations:

- The well-known port is reserved for P1. No other process can communicate with the service process using it till P1 is done.

- When the service process times out while P1 is preparing to send the second and final part of the message, we need to handle it without informing P1 that the first part has been ignored. P1 isn’t listening for incoming messages from the service process.

Since none of these problems arise without partial transfers, one solution is to ban them altogether. For example:

This is the approach taken in ARPANET where the communication to well known ports are restricted to short, complete messages which are used to setup a separate connection for subsequent communication.

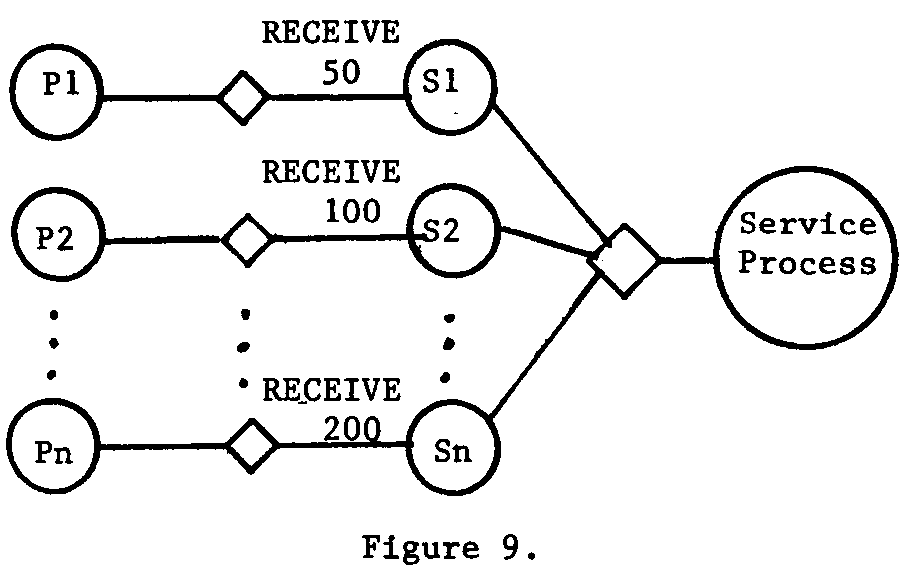

Buffer Processes

This solution is modeled around the creation of dynamic processes.

Whenever P1 wishes to transfer data to the service process, a new process S1 is created and receives messages from P1 till the logical message is completed, sleeping as and when required. Then it sends the complete physical message to the service process with EOM flag set. Thus no partial transfers happen between S1 and the service process, they’re all filtered out before that.

However, this kind of a solution isn’t possible with well-known ports. S1 is inserted between P1 and the service process when the connection is initiailized. However, in the case of well-known ports, no initialization takes place.

In discussing status returned to the users, we have indicated how the presence of certain other features limits the information that can be provided.> In fact, we have shown situations in which uncertain status had to be returned, providing almost no information as to the outcome of the transaction.

Even though the inclusion of insertion property complicates things, it is beneficial to use the weaker version of it.

Finally, we list a set of features which may be combined in a working IPCM:> (1) Time-outs> (2) Weak insertion property and partial transfer> (3) Buffer processes to allow> (4) Well-known ports — with appropriate methods to deal with partial transfers to them.